Why Diesel Prices Are Still High — and Why It’s Dragging the U.S. Economy Down

Current U.S. National Average Road Diesel Price

Why Diesel Prices Are Still High – As of the latest weekly data in January 2026, the U.S. national average on-highway diesel price sits at approximately:

$3.53 per gallon (weekly retail average)

This is the price truck drivers, fleets, farmers, construction operators, and manufacturers are paying at the pump nationwide. While headlines may suggest prices have “stabilized,” that stability exists at a level that continues to strain supply chains, suppress wages, and embed inflation across the economy.

Diesel has not corrected downward in proportion to crude oil, inflation easing, or historical norms. That disconnect is not accidental.

Why Diesel Prices Are Stuck at Elevated Levels

Diesel pricing is not driven by a single factor. It is the outcome of layered policy decisions, structural constraints, and global market pressures that collectively keep prices elevated even when conditions suggest relief should occur.

1. Crude Oil Costs (The Base Input, Not the Full Story)

Crude oil remains the foundational input for diesel fuel. Global crude prices respond to:

Supply controls and production targets

Geopolitical instability

Strategic reserve decisions

Coordinated output management by oil-producing nations

When crude rises, diesel follows. However, when crude falls, diesel does not decline proportionally. The spread between crude and diesel has widened over time due to downstream constraints, not upstream scarcity.

Crude explains the floor — not the ceiling.

2. Refining Constraints and Ultra-Low Sulfur Diesel Rules

Diesel requires more complex refining than gasoline, particularly due to ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD) requirements. This adds cost at every stage of production.

More importantly, U.S. refining capacity has been permanently reduced:

Refineries have closed or converted to renewable fuels

New refinery construction is effectively blocked by regulatory risk

Long-term investment has dried up due to policy hostility toward fossil fuels

Refineries that remain operational are running near capacity and enjoying historically high margins. When refining becomes the bottleneck, diesel prices stay high regardless of crude supply.

This is not a temporary issue — it is structural.

3. Diesel Is Exported While Domestic Users Pay the Price

The United States exports a significant portion of its refined diesel, particularly to:

Latin America

Europe

Regions affected by sanctions or refinery shortfalls

There is no domestic priority requirement for diesel fuel. Refiners sell to the highest bidder, and export markets often command premiums above U.S. trucking demand.

As a result, American truckers, farmers, and manufacturers are forced to compete with foreign buyers for fuel refined domestically.

That is not a free-market efficiency — it is a policy gap.

4. Taxes and Fees Were Never Rolled Back

Diesel carries:

Higher federal excise taxes than gasoline

State and local fuel taxes

Environmental compliance costs

Carbon-related fees in select states

None of these were meaningfully reduced during inflation spikes.

None were suspended to protect supply chains.

None are temporary.

Diesel is taxed as if it were discretionary consumption — not the critical infrastructure fuel it actually is.

5. Global Market Pressure and Coordinated Supply Control

Organizations such as OPEC continue to influence global oil supply by managing production targets that prevent prices from falling below desired levels.

Diesel, as a refined product, experiences amplified effects:

Supply cuts raise crude prices

Refining constraints magnify the impact

Export demand locks in higher pricing floors

Even strong domestic oil production cannot fully offset coordinated global supply control.

6. Government Data Explains the “What,” Not the “Why”

Agencies like the Energy Information Administration report:

Inventory levels

Weekly price averages

Regional price differences

What they do not address is why diesel remains expensive relative to historical norms, or how long this condition will persist.

A “stable” diesel price at $3.50+ is still economically damaging.

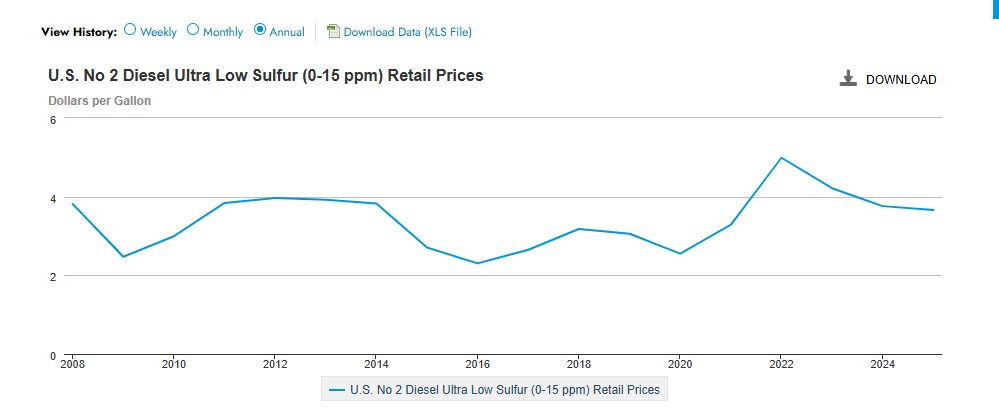

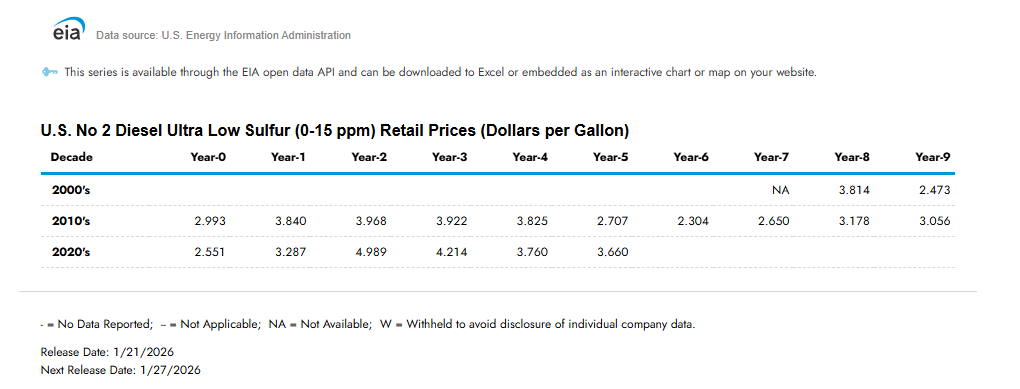

10-Year Diesel Price Trend: Normalized Highs

What the Last Decade Shows

Over the past 10 years, diesel prices have:

Established higher price floors after each spike

Recovered downward more slowly than gasoline

Failed to return to pre-crisis baselines after shocks

Key observations:

Post-2015 diesel prices never fully normalized

COVID-era volatility permanently reset pricing bands

The 2022–2024 spike created a new long-term floor

In practical terms, diesel has ratcheted upward — not cycled.

A 10-year chart shows fewer troughs and higher averages with each cycle, confirming that today’s pricing is not an anomaly, but a new baseline.

20-Year Diesel Price Trend: Structural Shift, Not Inflation

What Two Decades Reveal

Looking at a 20-year diesel price graph, the pattern is unmistakable:

Early 2000s: Diesel tracked closely with crude

Post-2008: Refining margins widened

Post-2015: Environmental and regulatory costs escalated

Post-2020: Capacity loss locked in permanent premiums

Diesel pricing has decoupled from inflation-adjusted historical norms.

Even when adjusted for inflation, current diesel prices are:

Elevated relative to trucking productivity

Detached from wage growth

Misaligned with consumer purchasing power

This is not inflation alone — it is policy-induced cost persistence.

The Economic Fallout No One Talks About

Trucking

Small carriers exit quietly

Independent drivers absorb costs without pricing power

Driver pay stagnates while operating costs rise

Capacity becomes fragile and volatile

Construction and Manufacturing

Material transport costs inflate bids

Projects delay or scale back

Productivity declines

Capital investment slows

Consumers

Grocery and retail prices remain “sticky”

Inflation never fully retreats

Cost increases compound invisibly through logistics

Diesel is embedded inflation. You don’t see it labeled on receipts — but it’s in everything.

Bottom Line

Diesel prices remain high because:

Refining capacity was allowed to shrink

Export markets are prioritized over domestic stability

Taxes and fees were never rolled back

Global supply is strategically constrained

Trucking has no political leverage

The system is functioning exactly as designed — just not for the people who move the economy.

Until diesel is treated as critical economic infrastructure, prices will remain elevated, margins will stay thin, and inflation will remain embedded across every sector that relies on transportation.